Flash-Decoding for Long-Context Inference

| Oct 12, 2023 | Written by Tri Dao, Daniel Haziza, Francisco Massa, and Grigory Sizov |

Motivation

Large language models (LLM) such as ChatGPT or Llama have received unprecedented attention lately. However, they remain massively expensive to run. Even though generating a single response can cost about $0.01 (a few seconds of an 8xA100 instance on AWS), the costs quickly add up when scaling to billions of users, who could have multiple daily interactions with such LLMs. Some use cases are more expensive, like code auto-completion, because it runs whenever a new character is typed. As LLM applications multiply, even small efficiency gains to the generation time can have a massive impact.

LLM inference (or “decoding”) is an iterative process: tokens are generated one at a time. Generating full sentences of N tokens requires N forward passes through the model. Fortunately, it is possible to cache previously calculated tokens: this means that a single generation step does not depend on the context length, except for a single operation, the attention. This operation does not scale well with context length.

There are a number of important emerging use cases of LLMs that utilize a long context. With a longer context, LLMs can reason about longer documents, either to summarize or answer questions about them, they can keep track of longer conversations, or even process entire codebases before writing code. As an example, most LLMs had a context length of up to 2k in 2022 (GPT-3), but we now have open-source LLMs scaling up to 32k (Llama-2-32k), or even 100k more recently (CodeLlama). In this setting, attention takes a significant fraction of time during inference.

When scaling on the batch size dimension, the attention can also become a bottleneck even with relatively small contexts. This is because the amount of memory to read scales with the batch dimension, whereas it only depends on the model size for the rest of the model.

We present a technique, Flash-Decoding, that significantly speeds up attention during inference, bringing up to 8x faster generation for very long sequences. The main idea is to load the keys and values in parallel as fast as possible, then separately rescale and combine the results to maintain the right attention outputs.

Multi-head attention for decoding

During decoding, every new token that is generated needs to attend to all previous tokens, to compute: softmax(queries @ keys.transpose) @ values

This operation has been optimized with FlashAttention (v1 and v2 recently) in the training case, where the bottleneck is the memory bandwidth to read and write the intermediate results (e.g. Q @ K^T). However, these optimizations don’t apply directly to the inference case, because the bottlenecks are different. For training, FlashAttention parallelizes across the batch size and query length dimensions. During inference, the query length is typically 1: this means that if the batch size is smaller than the number of streaming multiprocessors (SMs) on the GPU (108 for an A100), the operation will only use a small part of the GPU! This is especially the case when using long contexts, because it requires smaller batch sizes to fit in GPU memory. With a batch size of 1, FlashAttention will use less than 1% of the GPU!

FlashAttention parallelizes across blocks of queries and batch size only, and does not manage to occupy the entire GPU during decoding

The attention can also be done using matrix multiplication primitives - without using FlashAttention. In this case, the operation occupies the GPU entirely, but launches many kernels that write and read intermediate results, which is not optimal.

A faster attention for decoding: Flash-Decoding

Our new approach Flash-Decoding is based on FlashAttention, and adds a new parallelization dimension: the keys/values sequence length. It combines the benefits of the 2 approaches from above. Like FlashAttention, it stores very little extra data to global memory, however it fully utilizes the GPU even when the batch size is small, as long as the context length is large enough.

Flash-Decoding also parallelizes across keys and values, at the cost of a small final reduction step

Flash-Decoding works in 3 steps:

- First, we split the keys/values in smaller chunks.

- We compute the attention of the query with each of these splits in parallel using FlashAttention. We also write 1 extra scalar per row and per split: the log-sum-exp of the attention values.

- Finally, we compute the actual output by reducing over all the splits, using the log-sum-exp to scale the contribution of each split.

All of this is possible because the attention/softmax can be calculated iteratively. In Flash-Decoding, it is used at 2 levels: within splits (like FlashAttention), and across splits to perform the final reduction.

In practice, step (1) does not involve any GPU operation, as the key/value chunks are views of the full key/value tensors. We then have 2 separate kernels to perform respectively (2) and (3).

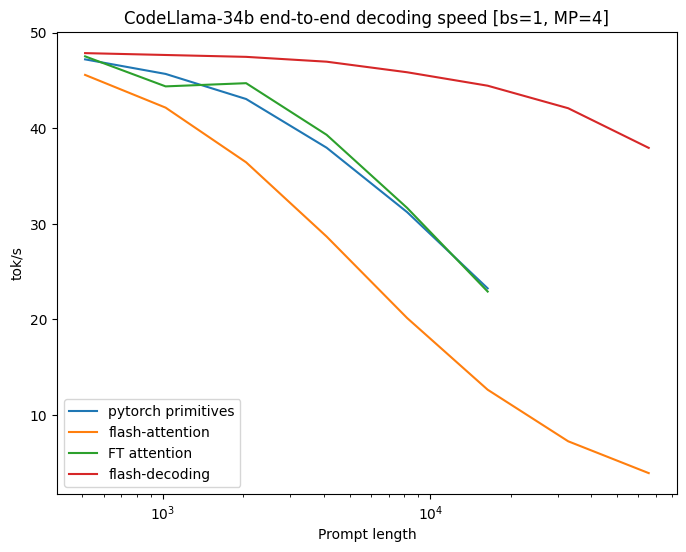

Benchmarks on CodeLlama 34B

To validate this approach, we benchmark the decoding throughput of the CodeLLaMa-34b. This model has the same architecture as Llama 2, and more generally results should generalize across many LLMs. We measure the decoding speed in tok/s at various sequence lengths, from 512 to 64k, and compare multiple ways of calculating the attention:

- Pytorch: Running the attention using pure PyTorch primitives (without using FlashAttention)

- FlashAttention v2

- FasterTransformer: Uses the FasterTransformer attention kernel

- Flash-Decoding

- And an upper bound calculated as the time it takes to read from memory the entire model along with the KV-cache

Flash-Decoding unlocks up to 8x speedups in decoding speed for very large sequences, and scales much better than alternative approaches.

All approaches perform similarly for small prompts, but scale poorly as the sequence length increases from 512 to 64k, except Flash-Decoding. In this regime (batch size 1) with Flash-Decoding, scaling the sequence length has little impact on generation speed

Component-level micro-benchmarks

We also micro-benchmark the scaled multi-head attention for various sequence lengths and batch sizes on A100 with inputs in f16. We set the batch size to 1, and use 16 query heads of dimension 128, for 2 key/value heads (grouped-query attention), which matches the dimensions used in CodeLLaMa-34b when running on 4 GPUs.

| Setting \\ Algorithm | PyTorch Eager | Flash-Attention v2.0.9 | Flash-Decoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| B=256, seqlen=256 | 3058.6 | 390.5 | 63.4 |

| B=128, seqlen=512 | 3151.4 | 366.3 | 67.7 |

| B=64, seqlen=1024 | 3160.4 | 364.8 | 77.7 |

| B=32, seqlen=2048 | 3158.3 | 352 | 58.5 |

| B=16, seqlen=4096 | 3157 | 401.7 | 57 |

| B=8, seqlen=8192 | 3173.1 | 529.2 | 56.4 |

| B=4, seqlen=16384 | 3223 | 582.7 | 58.2 |

| B=2, seqlen=32768 | 3224.1 | 1156.1 | 60.3 |

| B=1, seqlen=65536 | 1335.6 | 2300.6 | 64.4 |

| B=1, seqlen=131072 | 2664 | 4592.2 | 106.6 |

The up to 8x speedup end-to-end measured earlier is made possible because the attention itself is up to 50x faster than FlashAttention. Up until sequence length 32k, the attention time is roughly constant, because Flash-Decoding manages to fully utilize the GPU.

Using Flash-Decoding

Flash-decoding is available:

- In the FlashAttention package, starting at version 2.2

- Through xFormers starting at version 0.0.22 through

xformers.ops.memory_efficient_attention. The dispatcher will automatically use either the Flash-Decoding or FlashAttention approaches depending on the problem size. When these approaches are not supported, it can dispatch to an efficient triton kernel that implements the Flash-Decoding algorithm.

A full example of decoding with LLaMa v2 / CodeLLaMa is available in the FlashAttention repo here and in the xFormers repo here. We also provide a minimal example of an efficient decoding code for LLaMa v1/v2 models, meant to be fast, easy to read, educational and hackable.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Erich Elsen, Ashish Vaswani, and Michaël Benesty for suggesting this idea of splitting the KVcache loading. We want to thank Jeremy Reizenstein, Patrick Labatut and Andrew Tulloch for the valuable discussions. We also want to thank Geeta Chauhan and Gregory Chanan for helping with the writing.